Sea Power of Island Nations in 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities in Sri Lanka

November 02, 2020By Lieutenant Commander Roshan Kulathunga

Courtesy: The New York Times (A cargo ship navigating one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka)

The 21st century entire gamut of the nature of security is changing rapidly. Indian Ocean (IO) receives attention from state and non-state actors. Extra-regional countries such as the U.S., China and Japan are keen to have some presence in the IO. On the other hand, regional powers India and Australia are ardent and interested in maintaining her regional stability. They are interested in projecting Sea Power beyond their locale to garner economic and political sustainability in the world arena and where the IO is a major arena of competition.

These great powers have a keen interest over Indian Ocean island states, and their sphere of influence is inevitable. Sri Lanka is situated in a strategically important location in the Indian Ocean Region. This island nation could be categorized as a small state in the international system. According to Baldur (2014), there are four traditional variables in a country to call her as a small state: the number of inhabitants, the size of the territory, gross domestic product, and military capacity.

In this geopolitical context, it is interesting to understand the concept of Sea Power, relevant to island nation navies. Sea Power is the military and civil maritime capabilities of a country. According to Geoffrey Till, Sea Power is defined as the capacity to influence the behavior of other people by what you do at or from the sea. With the geographical location of Sri Lanka, all the main sailing lanes in the region are running closer to her. In an island nation, the Navy is the most vital maritime security component. Further, Navies and Coast Guards are two of the main constituents of Sea Power. Therefore, coastal states deem to strengthen with, notably, military naval capabilities.

Sri Lanka is an island nation; Land Power and Air Power are needed to amalgamate with Sea Power. Strategies are needed to develop with understanding the priority of the requirement for national security. Therefore, strategies are required to be developed by understanding the suitability of practice as a phenomenon, perspective and philosophy. Sri Lanka has the opportunities of maritime geography and maritime people. There are hybrid challenges of many non-traditional maritime security issues in the country. Most of the illegal physical infiltrations are flowing into the country through maritime environment. Therefore, the Sea Power of a nation projects her maritime power to eliminate maritime security issues.

The maritime nations have developed security strategies in history based on the perspective of maritime environment. They have given prominence to Sea Power, well, giving due prominence to Land Power and Air Power. What should be the strategic objective of a coastal state? It is essential to understand the significance of maritime resources, maritime economy and maritime people with coastal states’ strategic objective.

Establishing ‘Sea Power’ was one of the maritime strategies experienced and succeeded by the great maritime empires such as England. Admiral Mahan highlighted the importance of Sea Power, mentioning six elements namely, geography (access to sea routes), physical conformation (ports), extent of territory, population, character of the people and character of the government. Strategy developers need to understand these strategies and pass into practitioners in the field of maritime security.

Sea Power supersedes Land Power and Air Power on the concept of maritime security. The maritime historians, Admiral Mahan, Julian Corbett and modern maritime experts such as Robert Kaplan are highly recognized persons who are well versed in maritime power. Geoffrey Till is well verse about attributes at sea, as resources, the sea as a medium of transportation, the sea as a medium of information, the sea as a medium for domination.

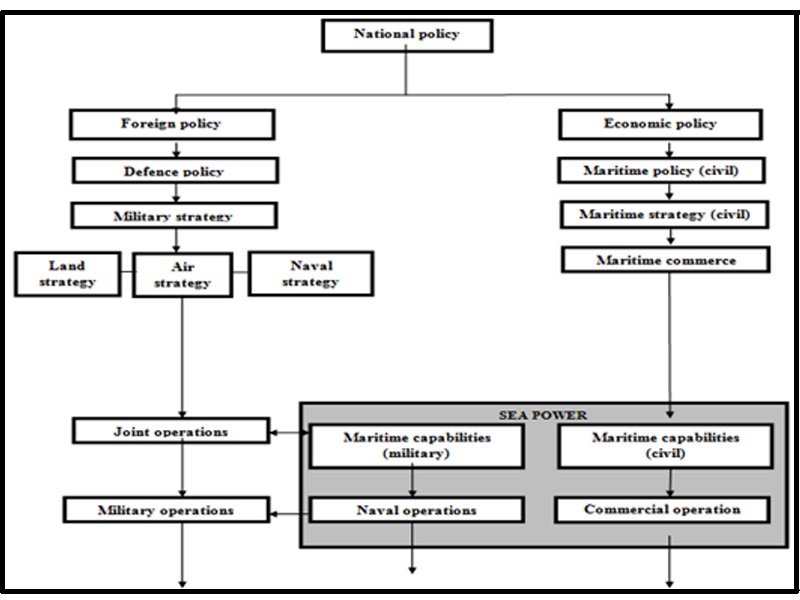

Courtesy: Sea Power, A Guide for the Twenty-First Century by Geoffrey Till

Establishing Sea Power in a country is directly helpful to strengthen the national policies. The Sea Power is a collective effect of a country’s military and civil maritime capabilities; thus, this could be achieved through naval and commercial operations. Military maritime capabilities are naval ships, crafts, naval surveillance systems and coastal protection units. Under civil maritime capabilities, merchant shipping, fishing, marine insurance, shipbuilding, and repairs are considered and a combination between these two elements is essential to garnering Sea Power for a country.

The great maritime historian, Alfred Thayer Mahan, understood the geostrategic importance of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). During the cold war, the United States of America was a maritime power, and the USSR was a Land Power. Lack of maritime expansion became a losing point for USSR to dominate the USA in the Cold War. Admiral Mahans’ maritime concepts were so influential in maritime studies. Most of the contemporary maritime security architectures are designed based on those concepts. These historical examples prove the gamut of nature, of a concept called ‘Sea Power’ and Sri Lanka being an island nation, these strategies must incorporate with security policies of the country.

Navies are an integral part of the maritime domain. In an Island nation, navies and coast guards should be the predominant security component to provide maritime security. We could take England, Australia, New Zealand and Japan as an example for strong island nations that can offer strong maritime security. In the IOR, island nations such as Mauritius, Sea Shells, and Sri Lanka are increasingly recognized as opportunities for maritime domain offers.

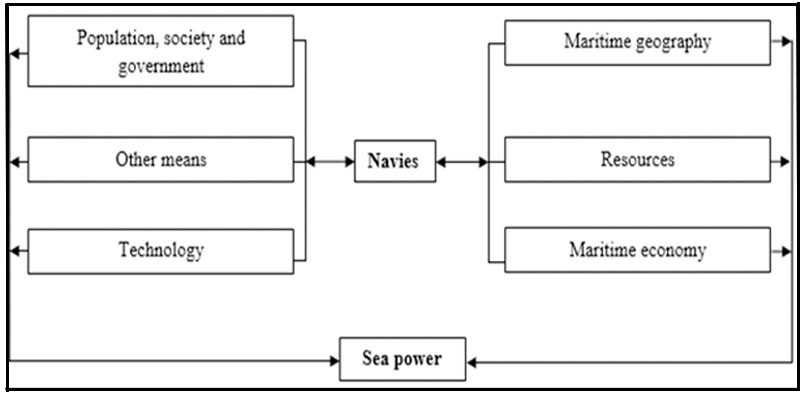

The constituent of Sea Power links together and helps determine the development of the country’s naval and maritime power.

Courtesy: Sea Power, A Guide for the Twenty First Century by Geoffrey Till, The constituent of Sea Power

Navies are linked with the constituent of Sea Power and interlinked to each other. These constituents have been used in the early Sri Lankan maritime domain. Sri Lanka had a great history as a maritime nation with archaeological proof of the voyages of King Parakramabahu, the greatest in the kingdom of Polonnaruwa . Thus, Sri Lanka is blessed with a rich maritime history.

In a maritime nation, people, society, and government are contributing to maritime domain development. Sri Lanka is a small state which has a greater opportunity to contribute to maritime-related activities. It is the responsibility of the policymakers to admire this and strengthen civil and military maritime capabilities.

The location of Sri Lanka in IOR gives an excellent maritime geographic opportunity of coasts, harbours, the proximity of essential sea lines of communication, and ease of access to the open ocean. In the maritime economy, Sri Lanka must give prominence to shipbuilding and repair, fisheries, marine insurance and ports. The eighteenth century Royal Navy grabbed their opportunity to be a strong Navy in the world. Therefore, it is a matter of choice for the authorities of Sri Lanka to decide how much money a country chooses to spend on the Navy.

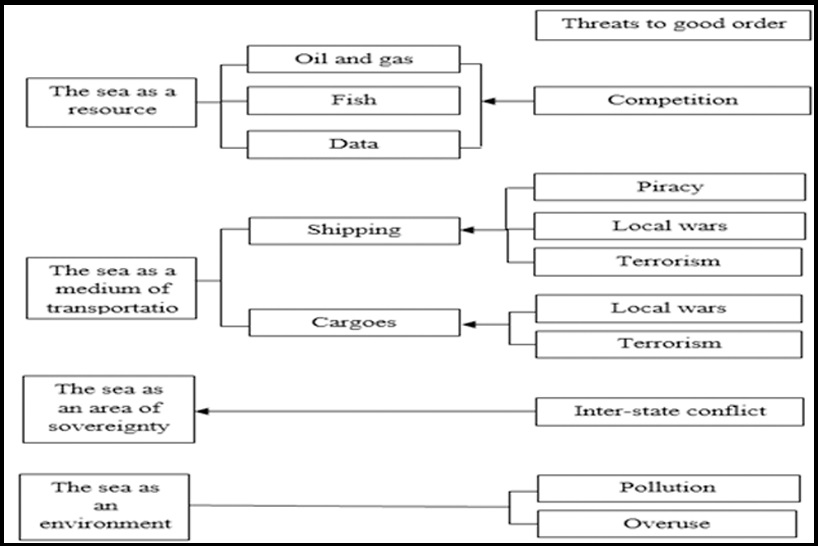

Geoffrey Till argues, main attributes at sea are vital pillars to maintain good order at sea. In the 21st century, maritime security is divided into a ‘home’ game and an ‘away’ game. Internal security issues could be addressed by the partnership of government departments, agencies and international partners, whereas to address external threats, holistically international maritime collaboration is required. The reason is present-day non-state actors engaged with transnational maritime crimes don’t consider any national boundaries in their operations. The following figure illustrates the main attributes and threats to good order at sea.

Sea Power, A Guide for the Twenty-First Century By Geoffry Till, Threats to the attributes and good order

Sri Lankan maritime security architecture must be strong enough to counter threats to good order at sea. The location of Sri Lanka in IOR has the mammoth of opportunities to use the sea as a resource to harvest fish, explore oil and data transit. On the contrary, the rivalry between state and non-state actors to the interest over maritime resources is notable in the IOR. In the view of Admiral Jayanath Colombage, the LTTE exploited Indian fishing trawler fleets, which were engaged in IUU fishing in northern waters of Sri Lanka to ferry their cadres, fuel, explosives and other war fighting materials mainly from South India to Northern, North Western coasts of Sri Lanka. IUU fishing is linked to transnational maritime crimes, money laundering and illegal trafficking of drugs. Therefore, there are many opportunities for smugglers to use IUU fishing as a shield to transfer illegal items into Sri Lankan Waters.

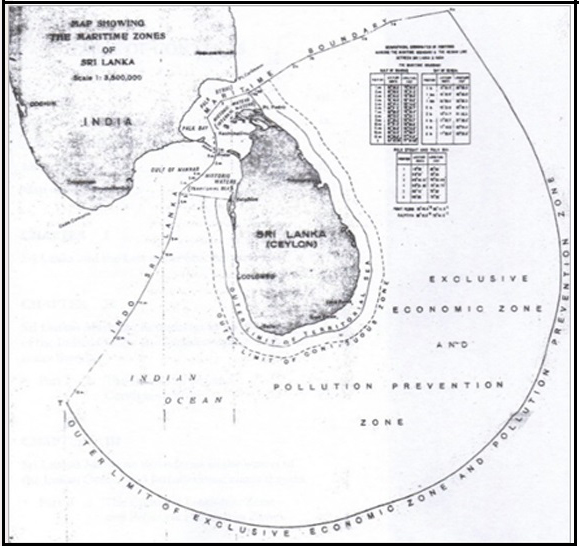

Sri Lanka is situated adjacent to one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. Around four nautical miles (one nautical mile = 1.852 km) south of the Dondra Head of Sri Lanka, ‘Traffic Separation Zone’ is marked, and it gives the directions and laws to the ships to operate in a massive ship traffic area. With the geographical location of Sri Lanka, all the main sailing lanes in the region are running closer to her. Therefore, the naval responsibility of providing maritime security and Search and Rescue (SAR) operation assistance is a leading role.

Courtesy: Maritime Boundaries in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka, and the Law of the Sea by N. Chandrahasan

The demarcation of maritime zones around Sri Lanka is very clear. However, the North and North West sea of Sri Lanka are vulnerable to Indian Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing influence. Even though IMBL has been imposed by law, there is a contradictory argument over the fishing rights of Indian and Sri Lanka fishermen. Therefore, sovereignty could be challenged by this issue.

The sea as an environment gives balance to marine ecosystems and which helps every creature on the earth. The Sri Lankan coastal area is vulnerable to erosion, damage to coral reefs, mangrove, sand mining, etc. Overuse of these natural resources could be negatively affected by the maritime environment. Further, pollution due to massive sea transportation could be a more significant challenge to Sri Lanka. Therefore, to counter aforesaid maritime security threats and challenges, a security mechanism must be developed to maintain the good order at sea.

Non-traditional maritime security issues are most notable in the current security environment in Sri Lanka, and the conceptual understanding of maritime strategies is vital to make a policy decision to address the issues described above. Therefore, maintain good order at sea, these maritime concepts must implement an Island nation like Sri Lanka.

-The Ministry of Defence bears no responsibility for the ideas and views expressed by the contributors to the Opinion section of this web site -